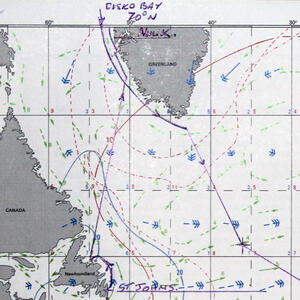

Our last photo story came from the Labrador Sea and ended as the Newfoundland coast vanished astern, headed on a bearing directly north in a general continuation of what was going to end up a clockwise circumnavigation of the Northern Atlantic that began thousands of miles ago on the Skeleton Coast – this leg would add another 900. For now the Artic region was both destination and voyage, the Greenland coast ahead a thin break between sea and ice.

Coastal voyaging around Newfoundland involves constant contact with ice, which drifts south from Baffin Bay – the sea that divides Greenland from the American continent – Artic breakaways, many from the eastern Arctic ice shelf driven south then north again by currents, and their cousins calved from Greenland glaciers. At sea it is a traffic problem something halfway between a shipping lane and a rocky archipelago. One never truly has the feeling of being mid-ocean as a route is picked between these icy behemoths, island hopping all the way from one coast to the other.

Midsummer is the sensible time of year for this sort of ‘cruise’: we were late and made landfall at the end of July, season of the midnight sun and never-ending sunsets which only flip, at some indeterminable point, into sunrise. This at least provides navigable light to safely thread a route north-west along the coast upon sighting it, more glacier and ice than coast really, while the sun burrows along beneath the terrain east to west.

Some of the transient yachts use Nuuk at the base for an attempt at the Northwest Passage, more and more accessible with every year – although still an unpredictable challenge with a turn-back just as likely as making Alaska. Peter’s friend Mike Thurston, on Australian Drina, left only the day after our arrival. Kiwi Roa would be back here another time for the same reason, but for now Greenland was the focus.

This collection of photos is spread over five pages. Boaters inspired by the following photo story should recognize that this is not a cruising guide nor navigational aid.

Landfall & Nuuk

Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, is some 300 NM north of the southern extremity, 10 miles in from the western coastline – and it is here we finally closed in with the land, entering into the calm waters of the enclosing fjord network.

A patrol vessel intercepted us a few miles away, sending a crew on a RIB to board and give us NORDREG instructions and customs and immigration forms – all very friendly and welcoming – and by the evening we were tied up in Nuuk harbour.

Ports in Greenland tend to be situated in indentations in rock where the bottom shelf is shallow enough to provide a workable depth for moorings and wharfs – and a surrounding topology that might provide foundations for housing. Access ways are miniature fjords, little channels cut through rock the sea has seen fit to fill with navigable veins a few tens or hundreds of meters wide, a fractal picture that looks much the same at a larger scale where the arteries can swell to five miles or more in breadth. The pattern only breaks at the boundaries, at the ocean outside, and inland where the icecap smothers everything.

Where these natural piers are insufficient, breakwaters and docks have been built at the scale for small fishing boats and runabouts. Kiwi Roa seemed out of place, neither small nor large, and the only solution is a raft five vessels deep: three yachts docked in parallel to two large trawlers, themselves moored to the wharf directly cliffside. 50 meters above, three large blue buildings perch on the ridgeline, a foundation of near vertical rock, two storeys of windows with a bird’s eye view of decks.

The Nuuk area has a multi-millennia history of settlement, as far back as the paleo-Eskimo, although it was deserted at the arrival of Viking explorers in the 10th century, with the Inuit coming shortly after. Both peoples appear to have lived locally with little interaction before the Norse disappeared again during the 1400’s. The modern city was not founded until a Dano-Norwegian effort in 1728 – founder Hans Egede gets a prominent statue visible from half the town. Most of the early founders were wiped out by scurvy and then smallpox, including Egede’s wife, a typically unhappy start to modern Greenland’s history. Now some 18,000 Greenlanders make up the population, the largest grouping on the largest island in the world.

The town is has a very neat layout. The plain it’s draped across is broken by rock, but is a relatively flat section of grass-topped plateau. From a map the deliberate roads and allotments together with the similar nature of the buildings creates the look of a military camp. There are no trees; only church spires and radio towers extend above the occasional two or three storey block. Space is used liberally, no pressure from overpopulation here.

After some five days we were ready to proceed north once more. From the water, even in bright sunlight, the Greenlandic towns have a habit of disappearing into the terrain, to the point they can be difficult to see. There is not quite the same look to them that seafarers will first imagine when recalling the sight of a city from sea. Buildings are dispersed widely, there is not the stand-out height to them, and colours are really more pastel than rumour and over-processed photos might have you believe – and their greenfield surrounds are not flattened and sharpened as with most cityscapes. It may just be that any manmade structure has a challenge competing with the elevation of the background terrain, but the feeling really is more that the settlement is still subject to its environment, man’s mastery of the land still a work in progress.

Back at the mouth of the fjord, as we exited the outer entrance, an old settlement is nestled on rock shoulders, half a dozen forlorn houses with holed roofs and missing timbers. This was to be the first of many redundant fishing hamlets, made superfluous by the modernizing effects of centralized townships and faster boats.

Kiwi Roa anchored in the deserted rock harbor.