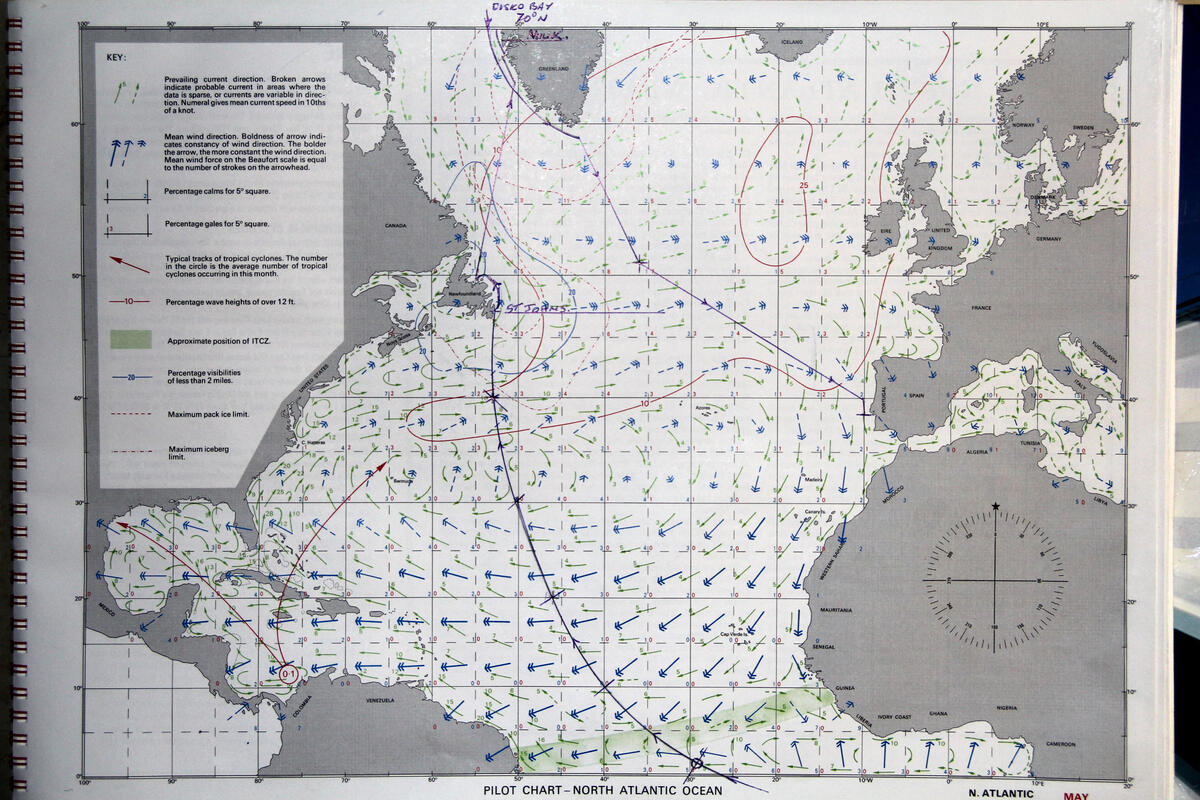

Kiwi Roa departed Ascension Island, heading ultimately for Newfoundland. The intent was to get back to the high latitudes and more adventures, this time northern rather than southern, and Peter didn’t want to dally with the regions in-between as the Caribbean and Americas had been visited years earlier. So, the pilot charts were consulted, and a route laid out where the prevailing winds might cooperate: 4,500 nautical miles up and across the Atlantic ocean.

The earlier parts of this crossing had already been completed, from the Namibian coast out to Saint Helena, and then to Ascension. There would be one more brief interruption: the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, some thousand miles into the passage, and the final leg north would take the total transatlantic miles to about 6,000.

Boaters inspired by the following Photo Story should recognize that this is not a cruising guide nor navigational aid.

Transatlantic

White tailed tropicbirds saw us off while Ascension receded astern. Winds were as expected: light to moderate southeasterly with flat seas. Kiwi Roa’s yankee and no. 1 genoa were set on twin poles, complemented with variations of a reefed main, and the wind vane tasked with the helm.

As we settled into the daily passage making rhythm, the occasional ship would appear on the horizon. One deviated from her course to pass close by our stern. Talking over VHF, the captain turned out to be a keen sailor looking forward to voyaging in his own sailing vessel one day.

We were visited by a variety of birds, including a migrating south polar skua familiar to us from the Antarctic.

Brown noddies in particular found us a convenient overnight transport from one hunting ground to the next. Like fighters returning to their carrier they would arrive around sunset to land, then in the falling darkness squawk and scrap amongst themselves over the ideal roost. Peter, annoyed with the prospect of harvesting guano from decks, would attack them with a boat hook. But the birds would not be discouraged. He eventually admitted defeat – and even looked forward to the company of these unpaying passengers.

On approaching the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone the waters became productive for a daytime lure. We hooked a couple of mahi-mahi (dolphinfish), horse mackerel, a rainbow runner, and to our distress a sailfish. Peter abhors game fishing: these fight to the death so it’s even worse to lose the fish once hooked, which we did, and it will almost certainly have died from its ordeal.

Some eight days and 1,050 nautical miles from Ascension, we closed with the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago during dark, and ghosted slowly in through the morning.

These isolated mid ocean rocks break the surface about 510 NM off the Brazilian coast. By claiming and occupying them, Brazil enlarges its marine economic zone many fold.

They make for a slightly surreal setting, buildings on jagged rocks and a moored ship, where by rights there should be nothing but ocean. A Brazilian trawler, apparently doubling as a support vessel, floated nearby, tethered by a warp to a buoy.

In anything other than a flat calm there is no feasible landing, so stopping to visit the Brazilian naval station was not an option for us. Kiwi Roa continued on.

The doldrums of the ITCZ proved relatively benign by past experience. We had to drop sail on occasion to protect them as steerage way was lost in the incessant roll. The usual thunderheads formed and threatened but no severe squalls followed through. Constant trimming and course changes for optimum wind saw us pick up the southeast trades in less than three days.

Once through the convergence zone our course was determined by inspecting the most recent pilot charts and comparing these with daily GRIB files downloaded via HF. The prevailing winds of the Azores High circle the middle North Atlantic, shaping our route for an optimum sailing angle with the apparent wind always just forward of the beam and started sheets for boat speed.

Peter laid out a series of waypoints at 10° intervals: the next on the route was adjusted periodically on inspecting each day’s GRIB file, with the general policy being to stay as close as possible to the basic rhumb line. This strategy worked well until we ran into the horse latitude variables unusually early at around 23° N bringing a freight train of low pressure systems across our northerly route, with ever changing wind directions and strengths. The remaining 1,500 NM of fluctuating conditions and accompanying sail changes were to prove taxing.

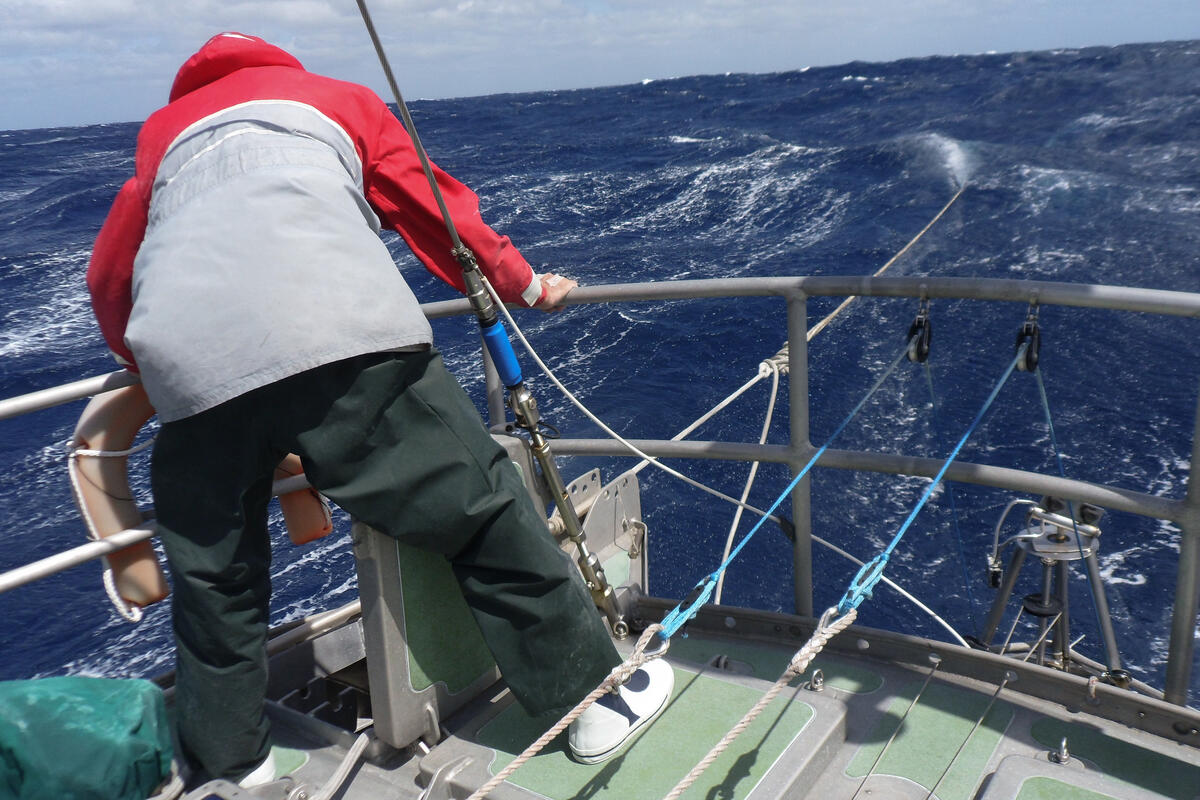

A big depression we could not escape rolled over us around 40° N 53° W. This system would stall, track south, stall again, then finally track back northeast towards Greenland – with Kiwi Roa on its western side for this whole sequence giving us gale force northerlies for four days. Rather than heave-to, which he does not consider a proper storm tactic, Peter decided to deploy the Jordan-type series drogue early to minimize the loss of hard-won northing.

The drogue worked well as we only lost 40 NM in the two days the boat ran on it. Several lessons were hammered home: about the forces of 10 meter breaking seas, which damaged the transom mounted Monitor wind vane; and about recovering the drogue while the leftover swells were still 5–8 meters. This was concurrent, sadly we later discovered, with the capsize of the British yacht Cheeki Rafiki and loss of its four crew, within only a few hundred miles of Kiwi Roa.

Pushing ever north with the North American coastline leaning in on us, the final four days of the passage were spent at 5–8 knots crossing the Grand Banks in unremitting fog so dense it was raining. With only radar for vision, landfall was heralded by the sound of powerful directional fog horns from navigation markers, lighthouses, and ships.

As we approached St. Johns, our chosen landing for Newfoundland, the fog receded seawards and a Canadian Coast Guard ship towing a disabled trawler loomed out of nowhere on our aft quarter.

A strange Newfie accent identifying itself as Harbour Control ordered Kiwi Roa into a queue of traffic entering and exiting the narrow entrance, and the transatlantic was complete.

Kiwi Roa’s stay at Newfoundland is narrated separately in the Newfoundland photo story. From there, the Atlantic expedition continued by way of Greenland’s west coast.